The Torah communicates in a way that is comparable to art. Art provides you with vivid, memorable images, and these images cause you to think and feel in a certain way. By making a connection between your past experience and an artistic depiction, art shapes your imagination, thoughts, and feelings. Today, I was struck by the way Deuteronomy 28 does the same thing. In fact, much of Scripture does the same thing, but I find this metaphor—“Torah as art”—a helpful way to think about what we are supposed to do with the grotesque depictions of curse in Deuteronomy 28.

Curse Art

Deuteronomy 28 is filled with rare vocabulary, and so it was my third reading in a row that set me to typing today—especially the twenty-second verse:

Here is what will happen if you do not listen to the voice of Yahweh your God, keeping and doing all his commandments and the statutes which I am commanding you today … Yahweh will strike you with deteriorating health, inflammation, fever, burning, sword, devastation, and discoloration. And they will pursue you until you are destroyed (Deut 22:15–22).

Verses like this are hard, especially when they come at you fifty-plus verses at a time (Deut 28:15–68). I asked my son at dinner if verses like this are things he would like to read in the Bible, and he looked up from his taco quickly to shake his head, “No.” Why, then, do passages like this exist? My thesis is this: They exist to help readers meditate on the end result of listening to a voice other than Yahweh’s voice. It is not enough to hear, “If you do not listen to Yahweh’s voice, you will surely die.” We need to ponder the result of going another way before we experience it ourselves.

The curses of Deuteronomy 28 concern the issue of disaster and disobedience, and I want to consider two other passages that deal with the same issue in slightly different ways. The issue of disaster and disobedience is at the heart of the snake’s crafty lies (Gen 2–3), and it is a topic that Jesus pointed his disciples to think about in a particular way, a somewhat artistic way (Luke 13:1–5). These passages provide wisdom for how we should think about disaster and disobedience, and I think the discussion below supports and illustrates the idea of Torah as art.

Disaster and Disobedience according to the Snake

Part of the snake’s trickery was to tell Eve that there is no connection between disobedience and disaster. The basis of the lie, the craftiness, has everything to do with the connection between disobedience, disaster, and time.

The snake tells Eve,

You will not “surely die!” (Gen 2:4)

This is pretty close to an outright lie. It can be a little hard to see the “craftiness” (Gen 3:1) in this part the conversation. The snake’s craftiness is much more on display in his first question (3:1), where he misquotes God’s instructions but does so in a way that implies that God is keeping good from Adam and Eve.

Did God go so far as to say that you can’t eat of any tree in the garden? (Gen 3:1)

Eve easily corrected this misquotation , but she bought the lie: God’s instructions are keeping something from me, something that is good for food, good to look at, and desirable to make one wise (Gen 3:6). Easy to see the craftiness here, but how was it crafty for the snake to say they could disobey with experiencing disaster?

The craftiness of Genesis 2:4—You will not “surely die!”—becomes more apparent when you remember that the snake’s reference to “surely die” (מוֹת תְּמֻתוּן, Gen 3:4) comes from Genesis 2:17, where God said that “on the day” or “at the time” (בְּיוֹם) you eat from the tree “you will surely die” (מוֹת תְּמוּת). The snake seems to know that בְּיוֹם means something closer to the vague “when” rather than “on the day”—something closer to בְּיוֹם in Genesis 2:4:

“… at the time Yahweh God made the earth and the heavens …”

It’s no wonder people have argued for so long over what “day” means in the first chapters of Genesis. The ambiguity of “day” is a core piece of the plot in Genesis 3. In Genesis 1, “day” (יוֹם) refers to a cycle of “evening and morning,” but in Genesis 2:4, יוֹם means something more like “at the time.” There has to be a play on words with יוֹם because Genesis 1 says the “heavens and earth” were made with six cycles of יוֹם, and Genesis 2:4 says “on the singular יוֹם when Yahweh God made the earth and heavens.” That’s at least part of the snakes craftiness: playing on the ambiguity of “on/at the יוֹם.”

The author’s point is that there is a connection between disobedience and death. He makes that point crystal clear when two chapters later, Adam does indeed die (Gen 5:5). The snake lied. The story of Genesis 2–3 provides a memorable, vivid mediation on the fact that disobedience and disaster do in fact go hand-in -hand. The story is different than the grotesque curses of Deuteronomy 28, but they help readers ponder the same topic—two different portraits, conjuring vastly different thoughts and feelings. My son would be happy to talk about the tricky snake in the garden, but he had no interest in talking about disobedience and inflammation.

Disaster and Disobedience according to Jesus

In Luke 13, there were some people interested in talking with Jesus about this topic:

There were some there at that very time telling [Jesus] about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their own sacrifices (Luke 13:1).

These people bring up the topic of “disaster,” and Jesus brings up “disobedience”:

And he answered them and said, “Do you think these Galileans were worse sinners than everyone else because this happened to them?” (Luke 13:1)

Apparently, Jesus cares about how you move mentally between these two topics: disaster and disobedience. His warning in this passage is to say, “Don’t draw a line too quickly between the two.”

No! I’m telling you that unless you repent you will all perish in the same way. (Luke 13:2)

Jesus doesn’t deny that disobedience and disaster are connected, but he warns these people not to make the mental move from seeing disaster happen to someone and then assuming that the person did something that was a direct cause of the disaster.

Jesus’s handling of this issue stands in sharp contrast to the snake’s. The snake said that if you don’t see a direct connection between disobedience and disaster, then there is no connection. Jesus says, there is most definitely a connection, but you must not think that you can clearly connect the dots. Snake: “The dots have to be connectable.” Jesus: “Don’t try to connect the dots based on what you see here and now. Just know there’s a real connection that will be apparent on the last day.” Jesus affirms the truth of Deuteronomy 28, and he helps us see something important: Deuteronomy 28 is not health and wealth, blessing for obedience and immediate disease and curse for disobedience. Health and wealth ideology quickly connects the dots in exactly the way that Jesus says not to.

Jesus pushes people to take a somewhat artistic, abstract move, from seeing disaster to pondering their own response to God’s voice:

If you don’t repent you will all likewise perish. (Luke 13:2)

Jesus says the best way to think about the disasters you witness is to ponder them like you ponder art: When you hear about disaster (and you can’t do anything to help those in need), let it inspire your imagination by serving as a vivid metaphor that helps you reflect on the consequences of disobedience in general. Disobedience leads to death (Gen 2–3), and you are not ultimately excluded from that cycle unless you repent.

Conclusion

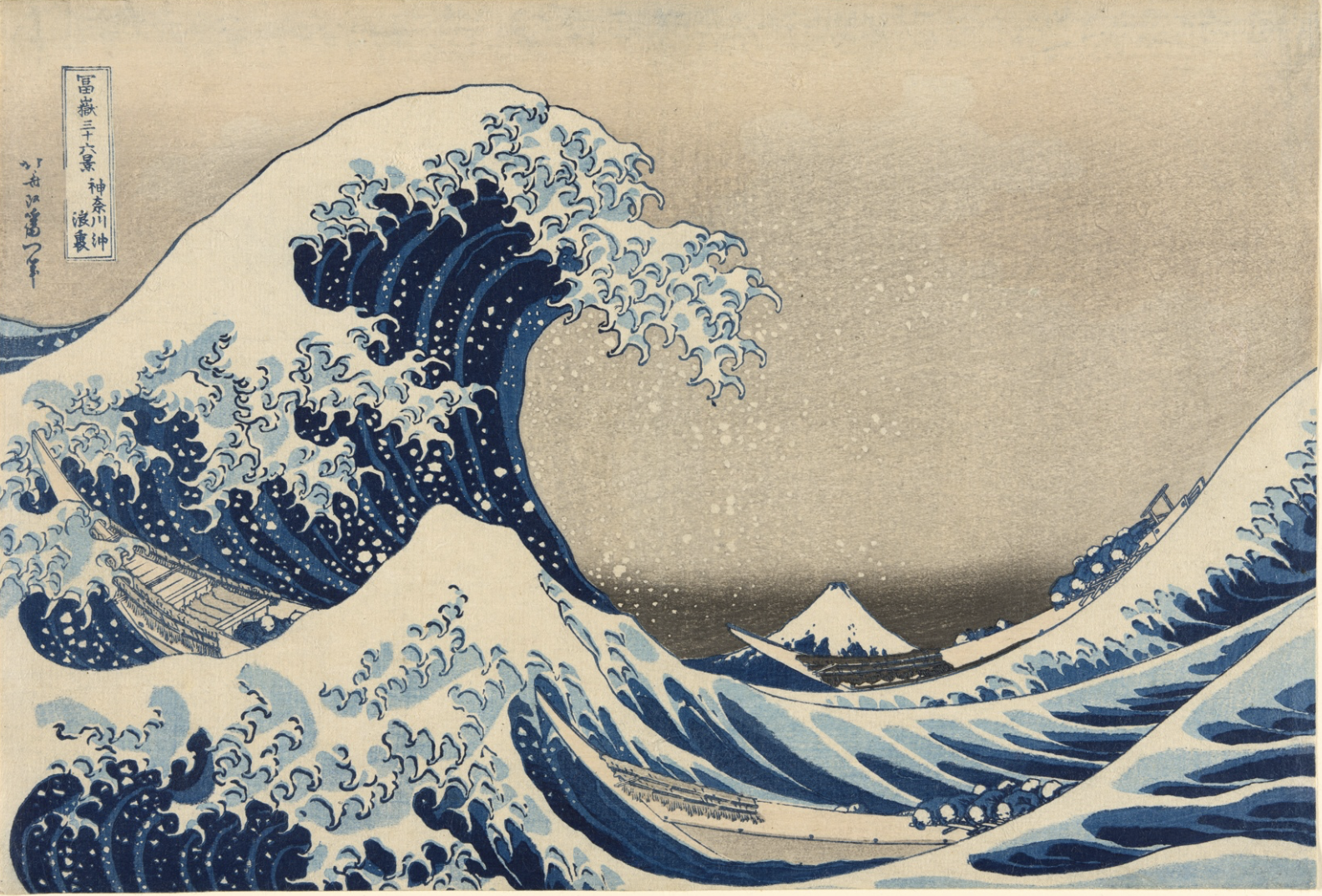

Jesus’s advice about how to think about disaster and disobedience fits well with the metaphor of Torah as art. The Torah’s grotesque depictions of curse in Deuteronomy 28 are tied tightly to disobedience (Deut 28:15). In light of Jesus’s advice, the dynamics of reading such a passage should be similar to the way one might stand in a Chicago art gallery and behold The Great Wave. We stare at the disaster, imagine its force, feel its fear, but without getting wet. Granted, there’s a distinct difference. The beauty of Hokusai’s Great Wave inspires awe and maybe even a smile, but Deuteronomy 28 can provoke sadness and thoughts that are hard to handle. There’s no way around that, but I do think the metaphor—Torah as Art—is a helpful way to think about what these passages expect from readers.

Leave a comment