This post is a record of my developing understanding of the Bible as a unified messianic book from start to finish, a book intricately woven together in the details and in the macrostructures by the hope of a coming one who would fulfill all of God’s promises to his people. Telling this story arises because of a reconsideration of that famous line in Judges: “In those days there was no king.”

This is two posts in one. It would be shorter and more palatable to break into two posts, but I woke up with all these thoughts streaming together in my mind. I think it’s better to get the whole flow of thought out in one post. Here goes.

Two Points

I’ve become increasingly convinced of two things. First, this oft-quoted statement from Jim Hamilton is spot on:

The Old Testament is a messianic document, written from a messianic perspective, to sustain a messianic hope.1

Continuing to read and teach the Bible every day, I am convinced that each and every book of the Old Testament is written to cultivate and sustain messianic hope in a Davidic king.

This leads me to the second point of this post: My previously stated take on the famous line from Judges is inadequate.

In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in their own eyes. (Judges 17:6; also 18:1; 19:1; 21:25)

In a previous post, I highlighted how Daniel Block helped me reread this line as a contrast between the people of Israel in the time of Judges and the kings of Israel in the book of Kings. Judges makes clear that both the people and the kings lead Israel to exile. The book of Kings itself makes crystal clear how Israel and Judah’s kings, from Solomon to Manasseh, gave up the land by abandoning God and his Torah. Judges makes clear that the people themselves played a huge role in this, too. I still think that this is true and part of the point of the author’s point in Judges, but there’s more to it.

If the entire Old Testament is written from a messianic perspective to cultivate a messianic hope, then that line from Judges says more. It critiques the people, for sure, but it also says we need the messianic king. Yes, of course, the people’s desire for a king rose from bad intentions. 1 Samuel 8 makes this crystal clear: The people first demanded a king so that they could be like all the other nations and be led by a flesh and blood king they could see. God had promised a flesh and blood leader would come since Genesis 3 and 12 and 15 and 17, all the way up to Genesis 49, but they didn’t want to wait for him any longer. They wanted a king now because left to themselves they were once again destroyed each other and their land.

But that’s just it: God had been promising a person would come since the beginning. From Genesis 3, through the promises to Abraham, and the forecast of Jacob in Genesis 49, God had promised a human being would come and rule in a way that Adam and Eve were always intended to. The messianic perspective of the biblical authors should get the last word on that famous line from Judges. “In those days, there was no king” means (1) the people are responsible for exile (just like the kings) and (2) we need the Son of David so badly, just like Psalm 2 says,

Blessed are all who take refuge in him. (Psalm 2:12)

In the rest of this post I want to sketch how my thoughts on point number one above have developed and led to this more robust understanding of the famous line from Judges.

The Messianic Perspective of the Pentateuch

No book on Old Testament theology has helped me more than John Sailhamer’s The Meaning of the Pentateuch. Most importantly, Sailhamer showed me how the poems of the Pentateuch function like a chorus that highlight the main themes in the intervening narratives.

In these posts, I’ve written about what I’ve learned from Sailhamer and from testing his idea through my own reading and teaching:

- Illumination through Analogy: Law and Narrative

- Themes & Thesis: The Major Poems of the Pentateuch

- Pentateuch Poems and the Intervening Narratives

- Torah as Art

I read Sailhamer’s book when it first came out in 2009, but for whatever reason at that time I wasn’t ready to receive what he was saying. A more recent rereading was illuminating to say the least. I’m more convinced than ever that from start to finish, the Torah was composed to cultivate and sustain the hope of a coming human being who will crush the head of the snake, fulfill the promises to Abraham, and bring an eternal kingdom through the line of Judah. The Joseph story is a long meditation on what that will look like.

Sailhamer helped me see the thoroughgoing messianic perspective of the Torah, and he helped me see how this hope was cultivated by Moses and the prophets, original author and final editors.

The Developing Messianic Job Description

Over the past several years, I have listened to everything the BibleProject has made (apart from a few new classes). I cannot overstate my gratitude for the BibleProject. It’s the best place for people to start learning how(!) the Bible is a unified story that leads to Jesus.

The BibleProject team gave me the helpful concept of a “developing messianic job description.” I don’t know where exactly they first used this language, but I suspect I encountered it first in their Torah series of podcasts, which begins here with Genesis.

An issue that stumped me for so long is this: The word “Messiah” is not used until later in the story of Scripture so how can people talk so confidently and explicitly about how each book is written to cultivate a messianic hope? Tim and Jon speak directly to this issue. They talk about how the hope of God’s people develops throughout the Torah, like a developing job description, and finally lands on a figure who is anointed, a Messiah, a promised king from the family of David.

Most importantly, through hundreds of hours of podcasting, you can taste the proof that’s in the pudding. What would it be like to read each book of the Bible as a unified story that leads to Jesus? You have a world of professionally produced audio and video resources to explore if you want great answers to that question.

One really great place to go and see how the author of 2 Samuel 7 funnels all the hopes of God’s people into and through the Messiah is this video from Jim and Sam on the Bible Talk podcast: 2 Samuel 7: On the Mountaintop of the OT, Talking about How the Bible Is Amazing (Bible Talk, #100)

Let’s move to the Former Prophets: Joshua through Kings.

The Messianic Hope of the Former Prophets

A few years ago, I began leading a team through writing a new course on the story of God from Genesis through Revelation. Teaching students about the way messianic hope develops across the entire Bible has and continues to be transformative for me.

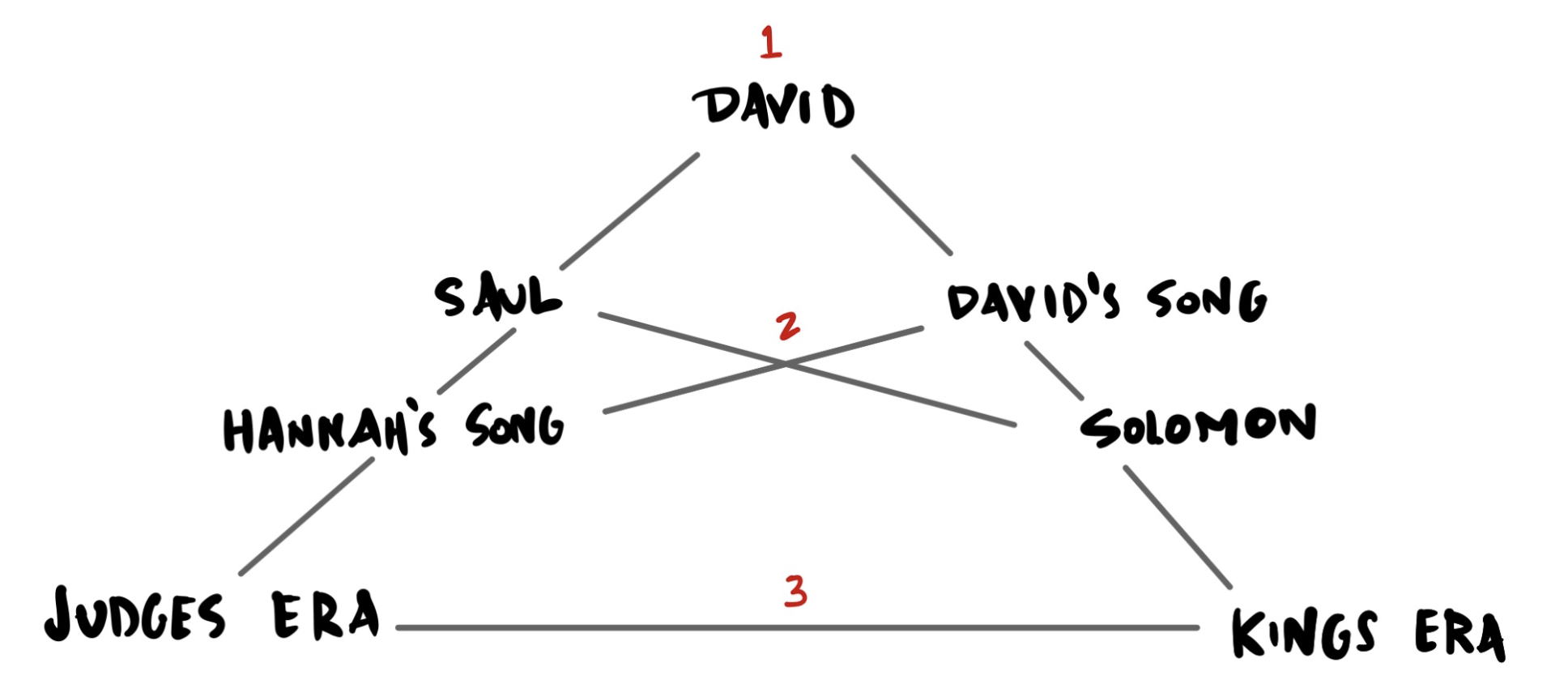

The following picture is something I sketched to overview the flow of the story from Judges through Kings. This picture encapsulates about ten lessons in that class:

At the bottom of the picture, level three, you see the way Judges and Kings are parallel. This brings us back to where we started above. Judges portrays the people of Israel as the downhill, growing snowball that led to the avalanche of exile, and the book of Kings makes plain how Israel and Judah’s kings were ultimately to blame. It was a joint effort. All were responsible for abandoning God and his Torah.

The second level highlights the way the hope of God’s people develops towards an anointed one. Saul and Solomon are the opposite of what the anointed one of God was supposed to be (Saulomon). David is the model.

You might push back on the idea that Solomon is a negative model because his life begins so well. Unlike Adam and Eve, Solomon asks God for wisdom to rule, and God gives it to him. Solomon leads Israel into peak flourishing. Nevertheless, Solomon does exactly what Deuteronomy 17 says a king shouldn’t. He brings in the idols, he worships money, sex, and power, and the kingdom never recovers.

The first level of the triangle highlights David as the model anointed one. David was far from perfect, but the book of Kings repeatedly looks back to David as whole-hearted — 1 Kings 11:4–6; 14:8; 15:3, 11; 2 Kings 14:3; 16:2; 18:3; 22:2.

The Hope of a Davidic Messiah in the Later Prophets and the NT

Over the past couple years, I’ve taken a deep dive into the the Later Prophets, and its clear to me that the promises made to David in 2 Samuel 7 — an eternal kingdom from his family — unites and unifies the Later Prophets.

I’ve written many posts on this site over the past couple years about the Minor Prophets, Isaiah, and Jeremiah. Here are a few of these posts that illustrate my thoughts on the way the prophets look back to the developing portrait of hope that starts in Genesis and culminates in David:

- The Kaleidoscope of Old Testament Hope in Isaiah 11

- Isaiah 19: The End of Our Story, the Goal of the Gospel

- Jonah as Interpretive Guide and Compass

- Habakkuk in Harmony with the Chorus of Biblical Hope

- Reading Jeremiah 7 and Meditating on the Messiah

The Later Prophets and the Writings look back at the story of the Torah and Former Prophets and cast visions of hope forward, visions of hope that have a distinctively David-shaped silhouette.

Patrick Schreiner is right on with this statement:

Monarchy is the chief metaphor Matthew employs to illuminate Jesus. The First Gospel presents Jesus as the Davidic king who leads Israel in faithfulness to the wisdom found in the Torah.2

One piece of this journey that I will leave out for the time being is my dissertation, which I hope to see published “soon.”

Conclusion

The way we understand the famous line from Judges (17:6; also 18:1; 19:1; 21:25) should be shaped by the messianic perspective from which the Old Testament authors write. The line says multiple things. First, it says that Israel abandoned the call of Deuteronomy. Moses spent thirty-three chapters calling Israel not to repeat the foolishness of the Exodus generation, but that’s what they did. It’s not just Israel’s kings that led them into exile. The problem started long before Israel had any kings. They abandoned God and his Torah.

Second, the famous line from Judges points forward to the ultimate hope of Scripture. The Psalms are framed by this very hope: Blessed are all who take refuge in God and his Messianic King (Psalm 2:2, 12). The ultimate author of Judges, the one who placed it in the growing collection of scrolls we now call the Old Testament and the Hebrew Bible, intended that famous line to be read as a pointer to messianic hope. We all need to take refuge in the Messianic King and meditate on his Torah. If we don’t, our lives will be turned to chaos and death, just like the era of the Judges.3

Footnotes

- James Hamilton, “The Skull Crushing Seed of the Woman: Inner-Biblical Interpretation of Genesis 3:15” in The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 10.2 (Summer 2006): 30. You can access the full article here. ↩

- Patrick Schreiner, Matthew, Disciple and Scribe: The First Gospel and Its Portrait of Jesus (Baker Academic, 2019), p. 101. ↩

- For more on how the book of Judges portrays Israel as a land of the walking dead, see the following: Jephthah’s Descension Offering and The Judges Autopsy. ↩

Leave a comment